- Twitch and YouTube are the dominant esports media brands, and are battling for market share

- Conventional TV wants to get involved, and is trying different routes, including acquiring esports content producers and creating its own content

- Challenges for conventional TV include: being authentic, lack of interactivity, different production conventions

- The role of publishers in broadcasting esports to fans is currently small and unclear

Streaming websites are synonymous with esports media viewing, and have been largely responsible for its rapid ascent. Twitch is by far the most important platform, averaging 10m views daily/400m views a month worldwide.

“Twitch owns the audience. To get reach you have to have a channel on Twitch,” says Malph Minns, Managing Director at sports consultancy Strive Sponsorship.

Other similar, but far smaller, esports video platforms include Azubu, MLG.tv, Hitbox, uStream, and StreamMe. The biggest competitor to Twitch is YouTube Gaming.

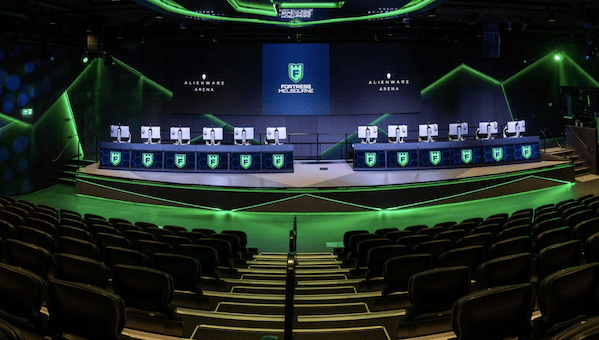

“There are really only two places for successful content creation – Twitch and YouTube,” says Matt Hill, SVP Global Sports and Entertainment Consulting, at marketing agency GMR. “[Put] simply, Twitch provides the gaming audience the ability to take their highlights to YouTube, and YouTube provides a notification to [gamers’ YouTube] channels when the creator is live on Twitch. The relationship is competitive in the sense that the two video platforms are both attempting to be the ‘go to’ location for gaming video content.”

Image: Example of a notification within YouTube that the gamer who produced the video being watched is currently live on Twitch

Each has its points of difference. YouTube attracts large global audiences, but lacked the ability to broadcast live until the launch of YouTube Gaming live streaming in September 2015, “a direct attempt by YouTube to dethrone Twitch,” says Hill.

“YouTube is adopting a very aggressive strategy to take share from Twitch in live streaming,” agrees Adam Mezhvinsky, founder of esports consultancy Quintessential Enterprises (QTE). “YouTube’s advantage is that is has a far wider social community for esports fans to share content with.”

According to Hill, a content creator can, and should, use both platforms, “as either one is a good choice when trying to grow your brand, and audience. YouTube now may be able to attract a wider, avid and casual, gaming consumer.”

Facebook, with 1.6bn users, is getting into the game by partnering with live video content providers, including Activision Blizzard Media Networks, to show live tournaments and news programming via MLG.tv’s Facebook page.

Television broadcasters have begun covering esports in a bid to reach its young male audiences. YouTube is adopting a very aggressive strategy to take share from Twitch in live streaming.

The conventional route is a dedicated TV channel. In the US, ESPN began by streaming games on its website, expanding its offer to includes blocks of esports programming on TV channels ESPN2 and ESPNU. European pay-TV broadcaster Sky recently launched the Ginx.TV channel to air esports competitions.

Another route is invest vertically. Turner Broadcasting and WME-IMG have done this by creating the Eleague around CS:GO. Coverage is distributed on TV channel TBS and simulcast on Twitch. The project was recently expanded to cover The Overwatch Open, a tournament based on Blizzard Entertainment’s Overwatch title.

Image: By Newzoo – most-watched content on Twitch, December 2016. ‘Esports hours’ is defined as ‘content from professionally organized esports competitions and does not include individual (pro-player) streams’.

This time it’s different

Traditional TV has covered esports before. In Korea, OnGameNet aired the first television broadcast of an esports tournament – Starleague – in 1999. MTV covered the Cyberathlete Professional League World Tour in 2005. USA Network showed the Major League Gaming 2006 Pro Circuit. Sky partnered with DirecTV to launch the Championship Gaming Series in 2007, which folded a year later.

The latest wave of coverage is considered more likely to be sustained because the esports audience has become a more critical target for traditional TV networks. This is a demographic which is showing less and less interest in traditional TV pay packages and schedules. Broadcasters have more at stake in getting their approach right.

The esports audience has grown to a scale that broadcasters and advertisers cannot afford to ignore. But they are struggling to get to grips with its global scale and lack of structure. Unlike conventional sport, esports grew online and without geographic boundaries.

“The rise of social media, live streaming and expanded distribution options for broadcasts of top level competitions have enabled esports to break down geographical barriers in a way that many traditional sports have struggled with,” says Mike Sepso, SVP at Activision Blizzard Media Network.

“eSport is global so distribution has to be global and Twitch serves that for the core audience,” says Michele Attisani, co-founder and COO at esports content producer FACE IT. “The big opportunity for broadcasters is to engage with a more localised mainstream audience.”

Alex Varatharajah, analyst at Ampere Analysis, says the main issue facing traditional media in esports is competing with established providers like Twitch.

Duncan Stewart, Deloitte’s Director of Technology, Media and Telecommunications Research, says broadcaster investment has not been significant:

“A typical US cable company might air 1,000 channels, so airing a single esport channel is not an overwhelming commitment. So far, based on public information as well as some private conversations, the eSport channels that have been launched have not seen blockbuster ratings. Part of the problem may be the human interest angle: people like knowing something about the person behind the player (think about how the Olympics always does that) and the people who play esports are sometimes not comfortable on camera.”

The importance of authenticity

Some historical attempts to put esports on television failed because the programming was perceived as inauthentic. “Too much of the old content pandered to a mainstream audience and alienated the core esports fan,” says Minns. “The challenge for broadcasters now is to provide value to the core fan while also trying to bring new people on board.”

This is also a challenge for esports content producers such as FACE IT, Ginx.TV, and ESL, whose business model is to distribute content to as many outlets as possible.

Too much of the old content pandered to a mainstream audience and alienated the core esports fan “Even two years ago, the hardcore esports enthusiast would only be interested in watching content on Twitch as the purest way of consuming this content,” says James Dean, Managing Director, Turtle Entertainment UK, the owner of ESL. “The aim is to adapt esports to TV. The industry is in a trial-and-error phase just now. There will be no single winning format but authenticity will be key.”

Broadcasters are often advised to partner with a ‘native’ esports producer to better understand the audience. Hence Swedish media giant MTG’s acquisition of Turtle Entertainment, and Sky and free-to-air commercial broadcaster ITV’s investment in Ginx.TV.

Interactivity missing from TV

A critical element which some observers suggest fundamentally undermines any attempt by TV to successfully deliver esports is the interactive nature of most esports consumption.

The real-time chat function is a key part of any online broadcast, offering people a very direct way to engage with their favourite players “The real-time chat function is a key part of any online broadcast, offering people a very direct way to engage with their favourite players,” says Dean.

Online platforms like Twitch offer viewers a rich set of statistics and the ability to switch between the video feeds of different players within the same game, or to switch to watch another game entirely. MLG.tv on Facebook offers viewers an ‘Enhanced Experience,’ which is an HD video stream with a feed of match statistics, live leaderboards, and insights based on the competition they are watching.

Such interactivity is increasingly possible on connected TVs, but more likely something that broadcasters will offer via second-screen applications or online services running parallel to the large screen broadcast.

Producing content for TV is different

“Traditional esports coverage has been like calling a horse race,” says Minns. “The action has been confined to commentary of player-versus-player with little broad narrative. Contextual storytelling is what broadcast does very well. Esports on TV will see more pre- and post-game analysis, putting the game in context and explaining an individual player’s story.”

ESL’s Dean agrees: “As the esports audience has grown, we are finding that people are looking for more engaging content, which means developing ideas around analysis and commentary and side stories that creates additional editorial or storylines around tournaments. The question is how we blend this into a service which works on second screen and on TV for the millennial audience.”

Attisani says educating viewers is key: “The biggest challenge with showing esports on TV is that viewers often won’t have a clue what’s going on. Education is vital.”

He suggests broadcasters could take direction from TV coverage of poker. “When poker was brought to TV the key presentation initiative was to show the competitor’s cards to the viewer at home with commentary about what each hand meant. Similarly, we have to explain what’s happening and why.”

An appraisal of the first season of Turner’s Eleague by rival esports broadcaster ESPN rated its production values “above that of other esports broadcasts”. It praised reaction shots of players and fans that provided emotional context to the in-game action, and the highlighting of the personal stories of some players, which “made the games more meaningful without sacrificing the pacing of the broadcast.” This allowed a newer audience to feel engaged with the players and teams, ESPN concluded.

There was criticism of the Eleague’s structure, however, with ESPN calling it a “drawn-out tournament” rather than a league, “with an unusually high number of teams and an unnecessarily inflated game count. As a result, it was difficult to become invested in any single game throughout the group stages, save perhaps the weekly Friday finals played on TBS.”

Eleague coverage is making a mark. An Eleague broadcast on 16 September 2016 drew 361,000 viewers, beating, by way of comparison, the 292,000 that watched the Premier League clash between Liverpool and Chelsea on NBC on the same day.

Video: Promo for Eleague’s CS:GO Major event

The role of publishers

Since games publishers’ business is selling games, rather than selling media rights to competitions featuring their games, there are far fewer content restrictions around major esports events than with traditional sports.

For the time being at least, publishers see esports primarily as marketing. The more people who spend time with their games via esports, the more people are likely to purchase the game or, for free titles, make micro-transactions within them. Ovum forecasts that global revenue generated by online/micro-transaction PC games – including LoL or Dota 2 – will rise to $28.1bn by 2019.

esports content producers, such as tournament organisers, meanwhile, make most of their revenue from sponsorship and advertising sold around video streams associated with their content. Adopting the structure, and indeed the terminology, of established sports further reflects the sense that esports are pitching towards the mainstream.

“We create thousands of hours of content from 15 studios worldwide, so we have a huge amount of inventory we can sell around and a big incentive to try and break into the broadcast industry and get our content into linear and OTT platforms,” says ESL’s Dean. “It’s the reason MTG bought us.”

For publishers and esports producers, the interest of traditional media represents potential new revenue, either by extending coverage of the game title to a new audience or in selling rights to broadcasters. Broadcasters will look to make money from sponsorship and advertising around programming.

“While the bulk of esports revenue for content producers is made at the elite end where the top teams and players compete, it is extremely important for publishers to feed the grassroots,” says Minns. “Publishers make more from game sales and in-game purchases than they make directly from fans watching the game. At least, that’s where the current balance of money lies.”

Recognising the increased interest in esports, publishers have sought to adopt the format of established sports tournaments to further their appeal to television and sponsor brands. Electronic Arts launched EA Majors based around Madden NFL Football, FIFA and Battlefield 1, explicitly intended to mirror the major tournaments in tennis and golf. There will be four Madden Majors a year, each with a $250,000 prize pool.

Valve scheduled four Majors for Dota 2, described as “a series of four marquee tournaments culminating in The International.” These Majors are backed up by open and regional qualifiers in multiple geographies.

Riot Games has hosted League of Legends championships across multiple territories for the fourth year in a row, including in France, the UK, Belgium, and Germany. “Adopting the structure, and indeed the terminology, of established sports further reflects the sense that esports are pitching towards the mainstream,” says Ovum.

****************

The esports viewer

Newzoo reports that esports enthusiasts spend 42 hours a month watching esports content, compared with 23 hours per month spent by football enthusiasts consuming football content. An average esports viewing session lasts 2.2 hours, according to Superdata. A large percentage of esports viewers (40 per cent say Newzoo) don’t themselves play the game that they like to watch, which is considered proof of a high level of engagement.

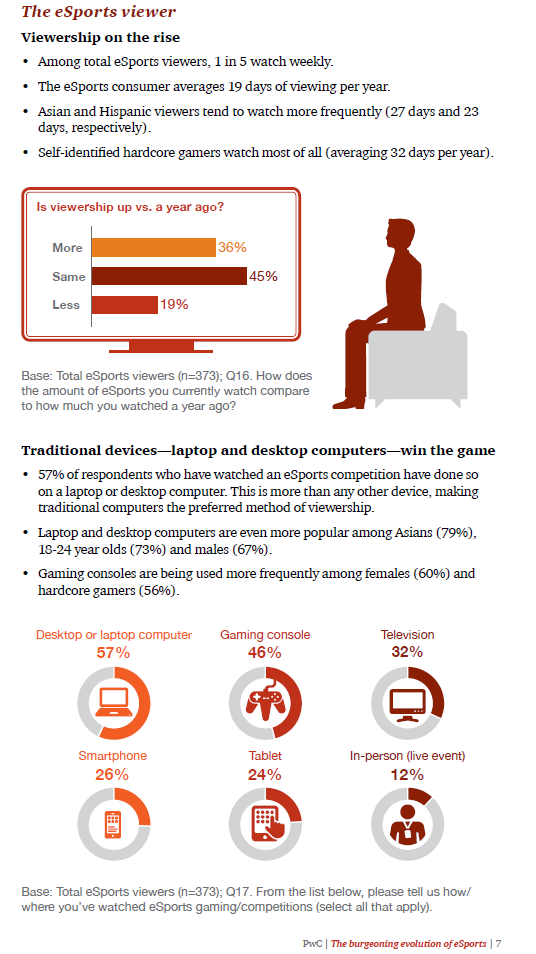

When it comes to what platform fans use, PwC says 57 per cent view esports via a laptop or mobile device. Only 32 per cent watch esports on TV. Newzoo research suggests that 67 per cent of US fans use laptops or PCs to watch esports video, compared to just 27 per cent for TV.

PwC on esports viewership:

This article was first published on Sport Business International on 31st January 2017.