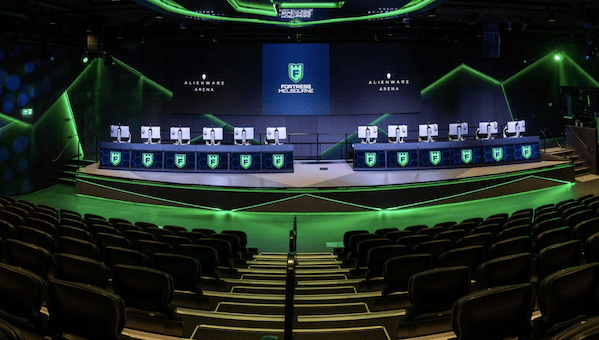

esports is big business. That is the message coming from the esports community, the majority of sports business conferences and both tech and mainstream media. Research companies like Newzoo, SuperData, Nielsen, Juniper Research, Repucom etc, and latterly the big consultancy firms of Deloitte and pwc, tell us that whichever way you want to measure it (participation, fan base, viewership, engagement, spend etc) the world of esports is only going one way – and that is up.

esports Audience Growth. Source: Newzoo 2016 Global esports Market Report

So why then is the question on everyone’s lips ‘how do you monetise esports’? If all the indicators of growth are there, why is it hard for esports businesses to keep their heads above water and justify the big investments from venture capital firms, wealthy private individuals and business?

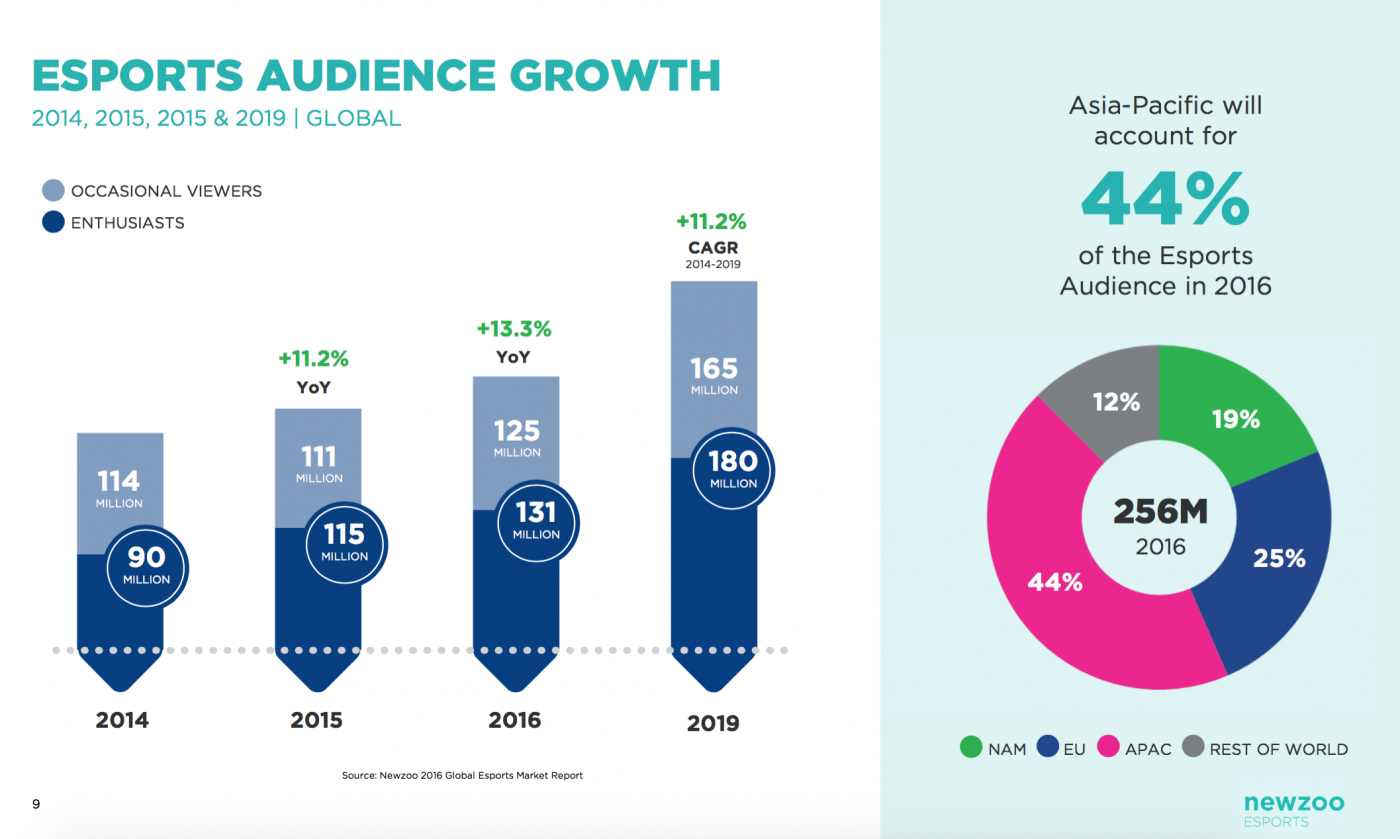

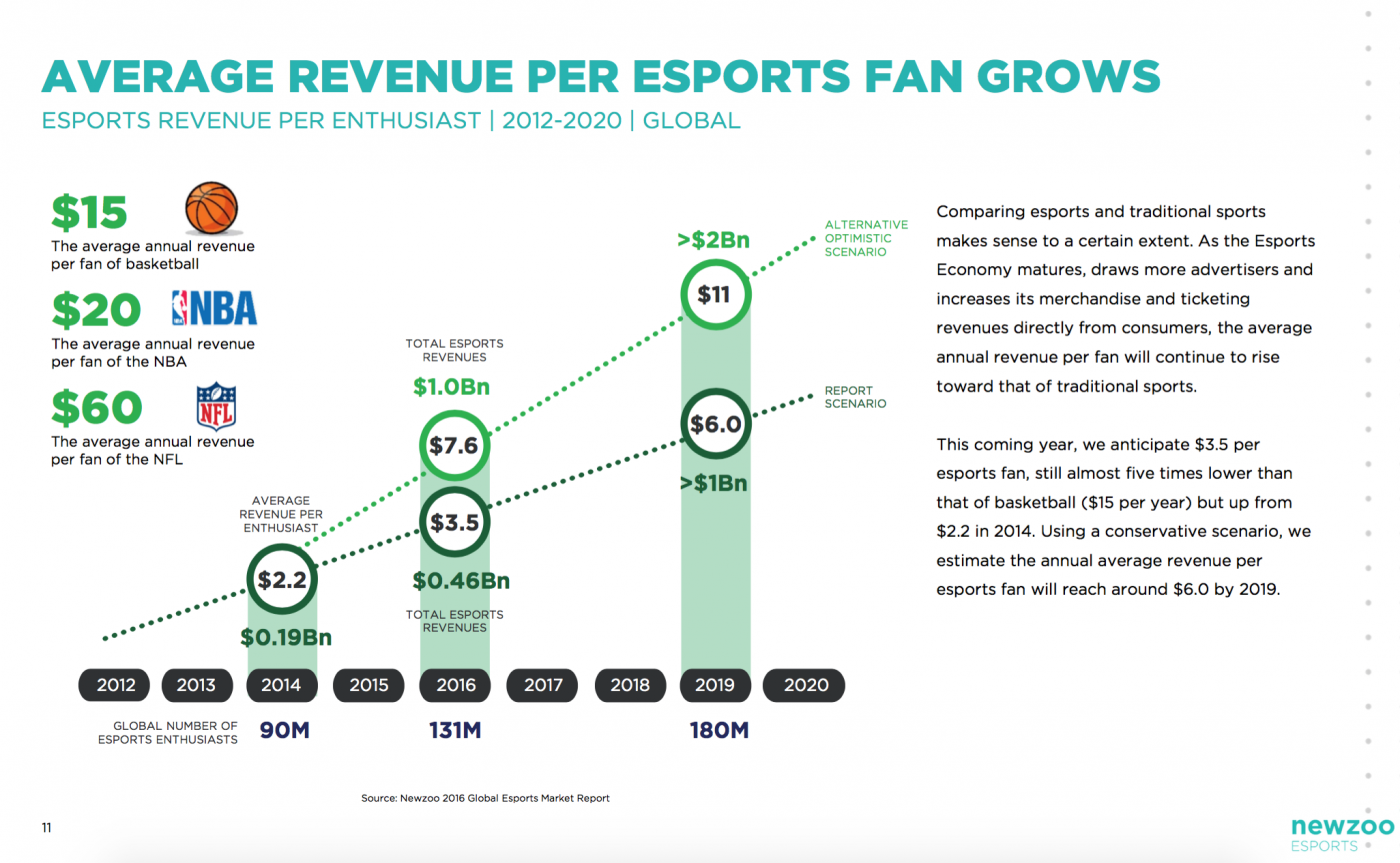

Average Revenue Per esports Fan. Source: Newzoo 2016 Global esports Market Report

Three ways esports can become an even bigger business

It was thinking about the answers to these questions that drew me to the recent LA Times story ‘Three ways esports can become an even bigger business’. In it LA Times journalist, Dave Paresh, sought the opinion of such esteemed talent as Kevin Lin (COO of Twitch, the game streaming platform that potentially has benefited most), Brandon Beck (CEO of Riot Games, arguably the leading games publisher in esports) and Gregory Milken (a venture capitalist who co-owns the League of Legends team, Immortals). The answers I came away with after reading their comments were:

- A still bigger audience (i.e. the migration of women participants to fans)

- A more structured performance pathway from grassroots amateur gamer, through competitive gaming to the elite level, and more protection for young players

- Sales of merchandise and broadcast rights

Now not for a minute do I believe that these were the only three factors identified as the way esports can become an even bigger business, nor is it important for the purpose of this blog (I intend to explore thinking further in subsequent pieces). However I assume that in conversations they were seen as the most pertinent issues presently, and therefore it is how they are perceived that struck me as maybe one of the reasons more money isn’t being made from esports. Let’s take each in turn.

The role of women

esports fandom is growing at a phenomenal rate with Newzoo predicting growth from 230m people in 2015, to an incredible 427m in 2019. The LA Times reports that “though women make up half of U.S. video game enthusiasts, only about a fifth of those who watch video game tournaments identify as women” (Nielsen). While audience scale is obviously important, and a bigger audience can only add to the monetisation opportunity, esports already has a huge audience it is largely struggling to monetise away from micropayments and advertising revenue. How will growing this still further (all be it making it more diverse and therefore, you’d think, appealing) help on its own?

What businesses with an interest in esports (or really in any sport) have to do is build a thorough understanding of both engaged and potential fans. This understanding needs to go beyond getting them to watch esports, to learning about what triggers best motivate them to engage further, what barriers block this interaction and what their consumption of goods and services is outside of esports. Once a deeper relationship has been established, monetisation will be far easier as what the audience values will be better understood.

In addressing the growth of the female fanbase specifically, the article details that gaming experts suggest part of the reason is that women tend to be heavier players of “casual puzzle and word games”. Twitch’s Kevin Lin points to having women’s teams and women only tournaments as initiatives to drive fandom, but admits that “the best approach for esports is unclear”. This is where I think not just esports, but all sports, can learn from the successful female engagement strategies of brands like Under Armour and Coca Cola. In Marketing Week’s article “How Under Armour and Coca Cola are overcoming ‘brand laziness’ in marketing to women around sport“, Under Armour‘s former European marketing chief Christopher Carroll points out that while men and women are equally as passionate about sport, their motivations and triggers for sport differ. He explains:

“[Brands] are not telling the right stories. Take the Olympics for example – it’s not just about the podium, but the journey of getting there. That is attractive to women, and that’s how you get to women’s hearts and minds and ignite a conversation.”

Understanding what different drivers motivate women, as oppose to men, is also made clear in Repucom’s Women and Sport report. Though focused on sports participation, it’s a useful reminder that what works for men won’t necessarily resonate with women. Men cite health and exercise, winning and new challenges as their main participation drivers. Whereas women are motivated by general health, rewarding, being around like minded people and weight loss. Equally the barriers to engagement are different. Male blockers are fitness, age and location whereas women are likely to cite emotional barriers such as fear of failure and embarrassment.

Insights into the growing rise and importance of female fans and female athletes

Christopher Carroll’s point of there being different reasons for sport engagement between men and women is given validation within esports from findings in pwc’s “The burgeoning evolution of esports” report. The report states:

“We see some of the biggest gender differences here. Men appear to be watching esports from a competitive lens — they not only enjoy watching their favorite games being played at the highest level, but they also watch competitions to improve their own game. Women,on the other hand, appear to watch for enjoyment — they truly enjoy watching the game and the social aspect that comes along with the competitions.”

The role of children

If I have understood Dave Paresh correctly, a more structured performance pathway (how a player or team rises from grassroots, to competitive gamer through to the elite levels) is required to not just organise the global competitive scene into a far more simple and understandable entity, but also to maximise monetisation. This makes sense to me and can only be effectively driven by the all-powerful publishers who control the game’s intellectual property (IP). However it requires a lot of work, as with esports organic growth has come fragmentation. The esports scene has been compared to the Wild West and any efforts to sanitise this into a performance hierarchy will not just be challenging to implement internationally, but will undoubtedly be met with resistance from businesses and people who don’t end up being part of the puzzle and/or who think it is better done a different way (usually a way that will benefit them more).

At the minute, at the elite level, there is the clean and consolidated Riot Games approach of total ownership of the elite scene, and then the model adopted by all the other publishers – a mix of owned and third party sanctioned/run events and leagues with little, if any, overall season narrative (although I expect this to change sooner rather than later through competition and consolidation). At the grassroots level however, the competitive environment is even more cluttered and confused with a plethora of operators in territories globally. Rather than owning and running this level of competition, publishers may be better served to act as curator and sanction existing leagues and events (based on clear criteria on how they are run) but assign them a place in the overall hierarchy of the competitive scene. These sanctioned competitions should be left to monetise (subject to the guidelines) directly. I doubt trying to manage this centrally, on a global basis, would be cost effective as monetisation at this level, in any sport, is hard and is usually funded by national, or even local, enterprises.

McDonalds Better Play. Making Grassroots Football Better

Often the best way to monetise the grassroots level of sports is through themed programmes that can be owned by brands as part of their corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes. ‘Doing good is good business’ is something I heard Sir Martin Sorrell say at a conference. Consumers are demanding that brands are more than just sellers of products and services and communicate a broader purpose with a social conscience if they want their consideration, especially amongst millennials. McDonalds is an example of a company who has a long running grassroots sport CSR programme with its Better Play scheme (helps to raise standards at grassroots football clubs through safety, advice, coaching for coaches, kit, support and recognition for volunteers), building on the historic McDonalds Coaches programme. Their CSR theme of education was extended through the company’s Olympics partnership with the training of London 2012 Games Makers. This is an area that the publishers can still own and control, whilst offering value to the grassroots elements of their communities.

World esports Association

On the flip side, there is a need for professional governance of the esports scene at every level. Common rules and regulations enable views and grievances, from all and any stakeholder, to be heard and dealt with. This has been well documented, and is even more topical after the launch of the World esports Association (WESA) this week. As we have seen in sports like athletics and football (with the troubles the IAAF and FIFA have recently faced) a lack of professional, accountable and transparent governance will likely result in a loss of confidence and the decision by sponsors to stop investing in the sport, or choose not even to invest at all. If esports is to be taken seriously as a competitive entity, and if it is to gain wider acceptance at the pace the community wants, then it is integral that it gets this right. When asked what tips she had for esports from a governance perspective at the Telegraph Business of Sport Conference held in London (UK) last week, Jane Purdon (Head of Governance for UK Sport) replied:

- Transparency

- Independence

- Have checks and challenge procedures in place

- Recruit a Board with broad and relevant skills, run by people who wouldn’t directly benefit from their decisions

She then suggested they speak to the Sport and Recreation Alliance about the voluntary code of good governance. The Code was designed to help sport and recreation to aspire and maintain good governance and can be downloaded from here.

The role of licensing

Merchandise sales will unequivocally appeal to engaged fans. This won’t be big bucks for every team and game, but for the most popular titles and teams it will offer a considerable revenue stream in time, if managed correctly.

Broadcasting rights on the other hand, well, I personally don’t think it is going to be the goose to lay the golden egg, and if it is, I think it’s some way off. I’d love to be proved wrong, but I just can’t see it. Why? Well the basic economic theory of supply and demand for one. A lot is written in the esports industry around this being a major source of revenue for traditional sports, and this I don’t dispute. But that doesn’t mean it will be a huge source of revenue for esports. Let me explain why.

The sports that make the biggest TV revenues, the English Premier League for instance do so for a combination of three main reasons:

- Their sport has a massive global fan base

- There is a limited supply of their product (entertaining football)

- They offer the best product in the marketplace

There are other football leagues that have teams with a large following and that can supply a football broadcast product, but none that is as premium as England’s. Fans want to watch the best players and teams play against one another in a competitive environment where results cannot always be predicted. Nowhere in football can you find that outside of the English Premier League. Sure, there are great teams and players in other leagues and a lot that are better than in the Premier League, however they are few in number and the majority of their league is weak, which makes for a less exciting football product. Instead their revenue is reliant on the local relevance of the teams and players to a national audience. esports isn’t bound by country boundaries, and as such doesn’t have the same level of national allegiance nor competitive infrastructure.

Few other sports or events command anywhere near the amounts of money that the English Premier League do. In fact a lot of sport you see on TV doesn’t get any broadcast income at all. It’s a battle for these sports to get a broadcaster to show their competition at all, with often the best that they can hope for being that the broadcaster agrees to cover the production costs in return for the sport being given an audience that they can monetise in other ways (e.g. larger sponsorship fees driven by a TV audience reach figure). As I am given to understand, the America’s Cup sailing race is one such long running global sports event that has struggled to raise money through broadcast rights historically.

The challenge esports has is there is a plethora of esports competition content and this is only growing as more events are held and more games titles are becoming esports. Whilst the whole esports audience may be huge and growing, it is the size of a specific game title’s audience that is more relevant when it comes to broadcast offerings. Add to that the fact fans are used to, and expect, content to be free, and there are already two big barriers. And that’s without even considering the challenges of getting millennials to engage through traditional broadcast for something they can, and have been, consuming online for years. The market fragmentation leaves broadcasters with a host of choices, which obviously works against broadcast rights monetisation for competition organisers. In addition broadcasters need and expect a coherent schedule that allows the audience to regularly engage over a period. This too is largely lacking in esports. If I was a betting man I would expect broadcasters to either acquire, or create, their own esports assets to monetise, rather than pay to show someone else’s. Whilst creating and owning traditional sports content is rarely an option for broadcasters, that’s not the case in esports.

Atlanta Braves baseball team

This would follow a similar model to Ted Turner’s famous acquisition of the Atlanta Braves baseball team in 1976. As the great author Malcolm Gladwell writes in his article ‘The Sure thing’:

“Turner’s Channel 17 was the Braves’ local broadcaster, having acquired the rights four years before… The team was losing a million dollars a year, and the owners wanted ten million dollars to sell. That was four times the price of Channel 17. “I had no idea how I could afford it,” Turner told one of his biographers, although by this point the reader is wise to his aw-shucks modesty. First, he didn’t pay ten million dollars. He talked the Braves into taking a million down, and the rest over eight or so years. Second, he didn’t end up paying the million down. Somewhat mysteriously, Turner reports that he found a million dollars on the team’s books—money the previous owners somehow didn’t realize they had—and so, he says, “I bought it using its own money, which was quite a trick.” He now owed nine million dollars. But Turner had already been paying the Braves six hundred thousand dollars a year for the rights to broadcast sixty of the team’s games. What the deal consisted of, then, was his paying an additional six hundred thousand dollars or so a year, for eight years: in return, he would get the rights to all a hundred and sixty-two of the team’s games, plus the team itself.”

Broadcasters are content creators, as well as curators, let’s not forget. They are familiar with building content propositions for audiences. There are currently relative low costs of entry for broadcasters to do this themselves and it offers them more control. It’s exactly what Turner Broadcasting has done with League. Traditional broadcasters just need to gain authenticity and permission to operate in this space. But that can be achieved in a variety of ways, including partnering with, or acquiring existing esports businesses. Even Twitch is going down the content owning, rather than broadcast rights buying, route. Their recent announcements around the Rocket League Championship Series (a collaboration with Rocket League games publisher Psyonix) and esports Championship Series (in partnership with gaming platform FACEIT and 20 elite teams) show that vertical integration is occurring, rather than monetisation by existing event and league operators.

Conclusion

- The role of women, children and licensing may be the key drivers in helping esports monetise more broadly and at scale, but some more lateral thinking may be needed to realise this

- Some of the biggest beneficiaries of esports monetisation may not currently be incumbent esports entities. esports businesses would be well advised to understand what opportunities there are for them to have a small share of something big, rather than a big share of something small (just having a presence in esports isn’t enough)

- There is still a lot of work to do, but the opportunity is potentially enormous

——————————————————-

Malph Minns is the Managing Director of Strive Sponsorship. Strive provides sponsorship advice to brands, rightsholders and agencies across sport, music, esports and film.

Read more about Strive Sponsorship’s unique approach and list of services here and follow Strive on LinkedIn and/or on twitter (@strivesays).

Please direct any enquiries to our contact us page.